Student reporters dug deeper into local news issues based on research presented at Is no local news bad news? Local journalism and its future, a conference held June 3-4, 2017 at Ryerson University in Toronto. Here’s what they found.

The front page of the Guelph Mercury’s final edition, marking the end of its 149-year print run in 2016.

By JASMINE BALA

Staff reporter

Guelph Mercury editor Philip Andrews didn’t know what to expect when he stepped out of the building into the cold winter air the day before the 149-year-old newspaper was to close. But it certainly wasn’t the large crowd standing before him and his news team, clapping and cheering as snowflakes the size of toonies drifted to the ground around them.

“There are periods in your life where you kind of feel like you’re acting in a movie,” Andrews said. “I felt that way after my kids were born, or you know, on [my] wedding day.” He had that same feeling as he looked around at the scene unfolding in front of him on Jan. 28, 2016.

The Mercury alumni and community members had just finished hugging the building when Andrews stepped out with members of his newsroom staff. They watched as someone from the crowd, acting as a town crier, recited a poem about news by John Galt, the founder of Guelph, Ont.

“There wasn’t a set agenda and this organic people moment just happened,” Andrews recalled.

As the poem came to an end, a call went out for the news staff to gather. Andrews and his team came together to take a bow on the front landing of the Guelph Mercury building. The newspaper’s general manager made a spontaneous speech thanking the Mercury’s readers. Then Andrews, holding back tears, told the crowd how grateful he was to have served the residents of Guelph.

Andrews and his team mingled with people afterwards. After lots of tearful goodbyes, editors and reporters returned to the newsroom to put the last issue of the paper to bed.

The crowd outside, however, wasn’t yet done. People wrote farewell messages on sticky notes and stuck them to the front door of the building, fully wallpapering it with reminiscences and condolences.

“It was history in the making and it wasn’t a terrible moment,” Andrews said. “It was an uplifting one. It was an informal, honest and emotional kind of farewell.”

A few days earlier, the TorStar-owned Metroland Media Group announced the Mercury’s closure, citing financial strains and declining readership.

“It’s ironic – the paper didn’t do well enough on a spreadsheet to remain but it certainly had a coterie of people who immensely appreciated the importance of doing local news service that the Mercury provided,” Andrews said.

The health of Guelph’s local news environment, he added, has suffered as a result of the closure. The city of more than 130,000 residents has one hyperlocal newspaper left: the Guelph Mercury Tribune, a twice-weekly community paper.

“The big deficit that I see is something of an absence of that inch-wide, mile-wide beat kind of reporting or the agenda setting reporting,” Andrews said in a recent interview, noting that he hasn’t seen a local story based on a freedom of information request since the Mercury’s closure.

“Doing good, deep, rich journalism takes time and daily newspapers had the staff and the inclination to do that almost as part of their identity and the value proposition that they had in terms of serving their communities.”

Guelph’s remaining media outlets now are “seeking to provide immediacy and doing a good job at that,” he added. But “in terms of that type of reporting that afflicts the comforted and comforts the afflicted – original reporting that isn’t just off what the institutions are seeking to have you look into – that isn’t there so much and that’s a problem for [the] community.”

Newspaper closures, however, aren’t unique to Guelph. When a daily newspaper serving Brampton, Ont. for 122 years closed in 1989, it left the growing community that is now home to nearly 600,000 people with only one newspaper, the Brampton Guardian, that publishes three times a week. Communities like Toronto, on the other hand, have multiple digital outlets, dailies and weeklies serving more than 2.7 million people.

“You need a news and information ecosystem that maps onto [local] geographies because political decisions are being made at that level,” said Philip Napoli, a professor at Duke University in the United States.

If people don’t have ready access to timely, verified news, he added, they can’t make informed decisions.

Researchers have been putting more and more effort into trying to develop a way to assess the health of local journalism and identify the characteristics of communities that are underserved and those that are well-served.

“Now, as the local journalism space seems so vulnerable, we are seeing…lots of foundations [in the United States] move into this space, realizing that they need to invest to keep these institutions viable,” said Napoli, who is principal investigator for the News Measures Research Project.

Napoli’s research on the state of local news in 100 U.S. communities is funded by the Democracy Fund, the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation and the Knight Foundation.

The goal of his project is to identify basic indicators that help foundations recognize which municipalities are underserved so they know where to direct their efforts.

Napoli’s team aims to confirm the risk factors they observed in an earlier pilot study assessing the state of local news across three cities in New Jersey: Newark, Morristown and New Brunswick. Some of the potential factors that differentiate a community that is well served in terms of access to local news from a poorly served community, they concluded, include per capita income, population density and size, proximity to a major media market, university presence, ethnic diversity and average level of education.

“We saw such a pronounced difference” in the three local journalism ecosystems after controlling for population size, Napoli said. Morristown is the smallest, wealthiest and least diverse of the three communities but was being served by “more and better journalism” and received a disproportionate amount of coverage compared to Newark, the largest, lowest-income and most ethnically diverse community. New Brunswick fell between Morristown and Newark in terms of its access to local news. In a paper about the project, Napoli and his team reported that Morristown had 10 times more local news sources and produced 20 times more stories than Newark.

“These findings,” they write, “potentially point to specific types of problems in local journalism, in which lower-income communities are dramatically underserved relative to wealthier communities.”

The general presumption about income, Napoli said, is that individuals in wealthy municipalities are more appealing to advertisers and have more to spend on journalism. But after conducting interviews with individuals running local news outlets, Napoli said he believes this is not the case.

“I think it’s more that these are communities where there are people who are in a position to start local journalism operations, financially,” he said. “Wealthier communities have more individuals that are in a position to do [journalism] as a public service, as a hobby – whatever the case may be – as opposed to in less wealthy communities.

“I’ll be very curious to see if those patterns hold up on a sample of 100 communities,” he added.

His team is using the same process that they tested in the New Jersey pilot study to assess their larger sample. Their methodology looks at the number of local news outlets in each community (infrastructure), quantity of news being produced (output) and quality of news (measured by locality, originality and whether it addresses a critical information need).

They have identified all of the online local news sites in the 100 municipalities and have used the Internet Archive, a digital library with a database of archived webpages, to create a week’s sample of content to analyze.

Napoli says he hopes to have the analysis completed and basic indicators of an unhealthy local news ecosystem identified by the end of the year.

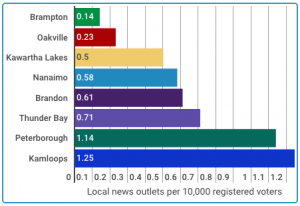

Indicators of Canadian news poverty from the Local News Research Project, as of fall 2015.

A similar study is being conducted in Canada by April Lindgren, associate professor at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism, Jaigris Hodson, assistant professor at Royal Roads University, and associate professor Jon Corbett from the University of British Columbia Okanagan. The Local News Research Project looks at various aspects of local news, including the differences in the availability of local news across the country.

Lindgren, director of the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre, said her interest in what she calls “local news poverty” began after she observed some communities in the Greater Toronto Area being better served in terms of local journalism than others. “We keep hearing about the closures and cutbacks at local media outlets across the country,” Lindgren said. “So, the concerns about those changes…and the availability of local news for people in the community was really what got us interested in the project.”

The Local News Research Project team has evaluated the local news ecosystems of eight communities in Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia and ranked them in a local news poverty index according to the health of their local journalism.

The health of each local news environment was measured by an earlier study they conducted comparing the coverage of the race for member of Parliament in each of those municipalities. They combined measures such as media concentration, the number of local news outlets per 10,000 registered voters, the number of local election stories per 10,000 registered voters and the percentage of these stories that were shared on Facebook to give each community an index score of how well served they are by their local news outlets.

Brampton had the lowest score of 5.01 on the news poverty index compared to Kamloops, B.C., which had the highest score of 14.62.

“So, now we know that Brampton, for instance, is this community that suffers most from news poverty and…[Kamloops] is on the other end,” Lindgren said.

Lindgren said her team is now in the process of creating a diagnostic checklist of risk factors for poorly served communities, though she acknowledges that eight communities may be too small a sample. Some of the factors that they will assess for possible inclusion on the checklist are income, education, diversity, major media proximity, internet access and population.

“We’re looking to see if there’s a correlation between different factors and the nature of the communities,” Lindgren said. “Low income is usually a factor for a community being at risk of news poverty. It could be that not having a local CBC station is a risk factor for news poverty. It could be that not having a daily newspaper is a risk factor.”

The checklist, she added, could be used by citizens to analyze what’s going on in their communities and help researchers prescribe solutions to news poverty.

Another Local News Research Project initiative is a crowd-sourced map tracking changes to the media landscape in real-time. The interactive digital map, which collects data going back to 2008, invites users to add markers recording changes like the launch, closure or merger of a news source.

As of June 2017, one year after the map first went live, about 56 per cent or 193 of the 347 markers document closures and 17 per cent (60) of markers indicate the launch of new outlets.

The Guelph Mercury has its own marker on the map, documenting its closure on Jan. 29, 2016. The last edition of the newspaper went out featuring a “-30-” on its front page, a symbol that journalists used to write to signify the end of their stories.

The “tradition” of using the symbol “faded as computers replaced typewriters in newsrooms,” the front page of the Mercury read.

The Mercury, however, wasn’t the only daily newspaper to close that day. On the other side of the country in British Columbia, the Nanaimo Daily News also printed its last copy. Its front page, just like the Mercury’s, featured a -30-.

Jasmine Bala

@JasmineBala_

Jasmine Bala is currently enrolled in Ryerson’s undergraduate journalism program.